Savoring the Sweet and Bitter Mystery of Life

The word humanist, although first applied in 15th-century Italy to those committed to the advancement of the liberal arts, later became synonymous with 19th-century educational reforms promoting classical studies and, more broadly, with arguments stressing the worthiness and potential of human beings separate from any religious tradition. It is in this context that any discussion of Lucas Johnson’s art must begin.

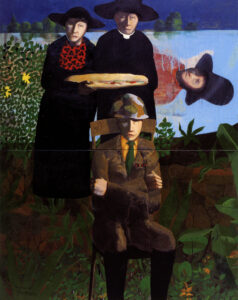

A self-trained artist and agnostic, in whose work the artist’s relationship with society is pervasive, Johnson became a painter to express himself first and foremost as a human being.

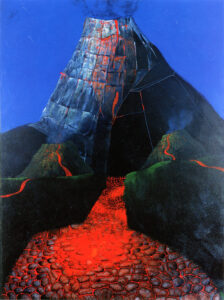

At its core, his work is a metaphor for the social condition — anexpression of an abiding preoccupation with what is human or, conversely, with what reveals a lack of humanity. It draws in equal parts upon imagination and memory, fiction and nonfiction, and by doing so, it revives the fortunes of contemporary figure painting, landscape, and still-life genres. It eschews purely formal and aesthetic considerations for ones rooted in universal themes concerning life and death, and spiritual values pertaining to good and evil. Stories and images from the past inform his art as vividly as do his rich experiences of events and people encountered on a daily basis.

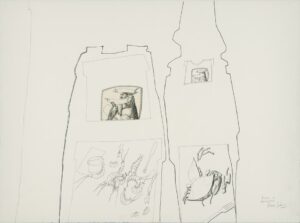

The genius of his art lies in the virtuosity of his pen, the subtlety of his tonal variations, and the dexterity of his brush, as well as in the power of his mind in conjuring forth subconscious images of exotic, if not sometimes bizarre, content. There are few parallels in American or even Mexican schools of art. For comparisons, one must return to “The Disasters of War” etchings by Francisco de Goya — or even back to the moral allegories of Pieter Bruegel and the phantasmagoric narratives of Hieronymus Bosch, on the one hand, or Caspar David Friedrich’s transcendental landscapes and even the monumentalizing still-lifes of Caravaggio and Juan Sánchez Cotán, on the other.

There are, by his own admission, three phases in Johnson’s artistic development: when he first confronted the mystery of life; when he began to make art to express what he understood; and finally, having explored what he understood, when he thought that he had fathomed the meaning of life’s mystery.

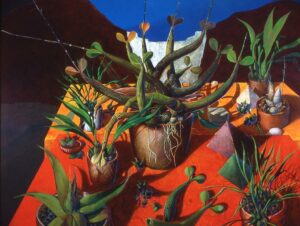

The capstone of his career is the long series of plant still-life paintings that he began in the 90s and that engaged his energies until his untimely death in 2002. These paintings sprang from a lifelong interest in plant forms, especially a passion for orchids. But they are not descriptions of the fleeting beauty of a blossom or the ephemeral charm of ripe fruit. Instead they document, even celebrate, the full cycle of plant life, from bud to blossom to withered stem. … In these paintings,upon which the artist was working when he suffered a fatal heart attack,one appreciates that he had fathomed the full meaning of the mystery of life, at once vibrant and beautiful, but bearing the seeds of its own demise.

The images and text — by Edmund P. Pillsbury, a former director of Southern Methodist University’s Meadows Museum (2003-5) — are from the book The Art and Life of Lucas Johnson, edited by Patricia Covo Johnson, Johnson’s widow and an art critic for the Houston Chronicle. The book was published by the Houston Artists Fund and the University of Texas Press. — (link to purchase)