About Gertrude Barnstone

To donate to HAF for the production of the book about Gertrude please click HERE.

In her will, renowned Houston artist and civic champion Gertrude Barnstone put a directive in all capital letters, to be executed upon her death: “I INSIST ON A PARTY IN MY HOUSE WITH FOOD AND DRINK.”

Barnstone wanted nothing to do with a solemn funeral or memorial service. Rather, Barnstone, who died December 24th, 2019 at the age of 94, demanded a joyous celebration of her life, a fitting tribute to a woman who channeled boundless creative energy into her signature sculpting designs and human rights advocacy.

Barnstone’s family and friends will gather this week to fulfill her request, honoring the legacy of a Houstonian whose eclectic metal artwork resides in homes, parks and public spaces across the city. A dynamic, fiery creator with a sharp-left activist streak, the former Houston ISD school board member carved out a unique place in the city’s civic culture, a Depression-era native who never strayed from her roots.

“She was a very free spirit, a fighter, and lived life on her own terms, hell be damned,” said Barnstone’s daughter, Lily Wells, likening her mother to “a combination of a grand dame and Blanche DuBois.”

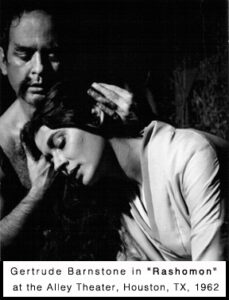

From the age of 7, when she started lessons at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, through her twilight years in Montrose, Barnstone expressed herself creatively through multiple mediums: acting, dancing, painting and, ultimately, sculpting. Her fondness for metallurgy, exhibited in bright, flowing, lyrical works, resulted in a decades-long career as one of Houston’s preeminent artists.

“So many people came to Houston who became artists. And a lot of artists from Houston, even though it’s wonderful here, decided they had to go to the big city,” said Randy Tibbits, coordinator of the Houston Earlier Texas Art Group. “In that regard, she was something of a rarity.”

Art alone, however, could not quench Barnstone’s passion. In the mid-1960s, angered by staunch conservative resistance to desegregation in HISD, Barnstone won a seat on the district’s school board. While her five-year tenure resulted in relatively few policy changes — she and the district’s first two black trustees, Hattie Mae White and Asberry Butler, were not in the board’s majority bloc — her activism helped pave the way for integration victories in the 1970s.

“My mother was a wonderful, beautiful idealist who sought to make the world a better place,” said her son, George Barnstone. “She worked as a volunteer to improve the lives of everybody.”

Born in Houston in 1925 to Arthur and Gisella Levy, Gertrude displayed an uncanny proclivity for personal expression throughout her childhood. Under the tutelage of Houston’s leading artists, and with a strong push from her highly-educated mother, Levy charmed audiences in the city’s top dance and theater productions while earning acclaim for her preternatural drawing skills. Meanwhile, her father, a petroleum engineer for the former Humble Oil, instilled in his only daughter a strong sense of fairness and equality amid continued segregation in the South.

Levy graduated from Rice University and briefly moved to California for her first marriage. Following a divorce, she returned to Houston and met architect Howard Barnstone, who would later gain acclaim for co-designing the Rothko Chapel. They wed in 1955 and melded into Houston’s burgeoning culture scene, as his career and her political activism gained steam.

Inspired by White’s advocacy and her involvement with her children’s schools, Barnstone ran for the HISD school board in1964. In his book, “Collision: The Contemporary Art Scene in Houston, 1972-1985,” local historian Peter Gershon wrote that Barnstone’s conservative opponent “was so sure of his victory that he’d failed to campaign and spent the summer in Europe.”

Barnstone prevailed in her election, pushing for integrated classrooms, free lunches for lower-income children and greater access to the arts. Opponents of racial integration sought to intimidate her, to no avail, Wells said.

“We had a cross burned on our yard. People would call and threaten and say horrible things,” Wells said. “She would say, ‘God bless you,’ and hang up. I think it energized her.”

Following Barnstone’s departure from the board, four HISD board candidates running on a pro-integration slate swept into office, ushering in major parts of Barnstone’s platform.

The end of Barnstone’s tenure coincided in 1969 with her divorce from her husband. She promptly took over production of “Sundown’s Treehouse,” a weekly children’s show on KPRC-TV, for four years.

In her final political foray, Barnstone lost a race for the Texas Senate in 1972 to John Ogg, a longtime elected official and father of current Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg. While Barnstone abandoned her political aspirations, she remained an active leader in the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas and multiple organizations dedicated to women’s and human rights.

Barnstone in the mid-1970s turned her attention more toward her artwork, taking classes in welding to open a new avenue for expression. Following more than a decade of manufacturing skylights for Southwestern Plastics, Barnstone struck out on her own as a full-time artist, working out of her bungalow on Yupon Street.

Barnstone specialized in freestanding pieces, gates, fences and railings, with much of her work landing in the homes of patrons. She worked into her 90s, persisting even after a fall in 2006 left her with only one functioning eye. While she sketched designs and welded smaller pieces. her assistant of about 30 years, Raynaldo Castro, performed heavy-duty tasks. “I tried to protect her, keep her from doing all the other stuff, but it didn’t slow her down at all,” Castro said. Barnstone is survived by her three children — George, Lily and Dora Cantwell — as well as five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Per her clear orders, there will be no funeral or memorial service.

jacob.carpenter@chron.com

================================================================

When her mother instructed Houston artist and activist Gertrude Levy Barnstone (now 89) never to marry or have children, the blue-eyed six-year-old promised herself that, dammit, she’d do it all. “You’re going to be an artist,” Mrs. Levy told her daughter. “Put down that broom.” And, for the last 89-odd years Barnstone has been busy making good on her promise. The arts were booming in Post-Depression Houston. New museums, theaters and orchestras were sprouting as fast as oil companies. Gertrude attended Houston public schools, took classes at the art school of the Museum of Fine Arts, and graduated from Rice University in 3 years.

A stunning dancer, actress and painter, Gertrude continued to draw, paint, sculpt, and act in local theater after marrying Howard Barnstone, a rising architect fresh out of Yale. The Barnstones befriended contemporary artists, attended museum and gallery openings and contributed to the founding of the Contemporary Arts Association. Among their friends were sophisticated art patrons and collectors, including John and Dominique de Menil, Charles Barnes and Marguerite Johnson, Claire and Sam Sprunt.

Barnstone was always an activist. She volunteered at Poe School when her three children attended and founded a Montessori school. Barnstone occasionally shifted her focus from art to politics. In 1963, angered by the conservative Houston School Board’s attack on its lone African-American member, she ran at large for a place on the Houston School Board which had, in 1963, been blocking integration for a full 10 years after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed Separate but Equal in the 1950’s. Howard Barnstone supported Gertrude’s School Board campaign, as he had supported her art. “He never wanted a stay-at-home wife,” she says now. She ran at large, wore out 8 pairs of shoes and won by 30,000 votes. While on the School Board Gertrude cajoled, argued and pushed the stubborn conservative block towards full integration.

In 1965 the Barnstones’ marriage burned itself out, the bonfire fueled by Howard’s resentment of Gertrude’s public accolades, love affairs (his and hers) and finally by Howard’s mental breakdown.

Through the sturm und drang Gertrude preserved her smile and kept her footing. She enrolled in welding classes and went to work part time for a company making skylights. Since their divorce in 1965 Gertrude has been making a living by creating vivid and lyrical sculpture, much of it architectural. Her garden gates, chairs, railings, tables and screens have enlivened Houston’s landscape. But it’s her spirit, vivid, lively, and above all indomitable that she’s given us. Once I asked her why she went into politics in the first place.

“I looked at myself in the mirror and decided I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t run,” she said. “Act or fold your tent.”

Words to live by.